Date uploaded: 2021-08-17 17:09:31

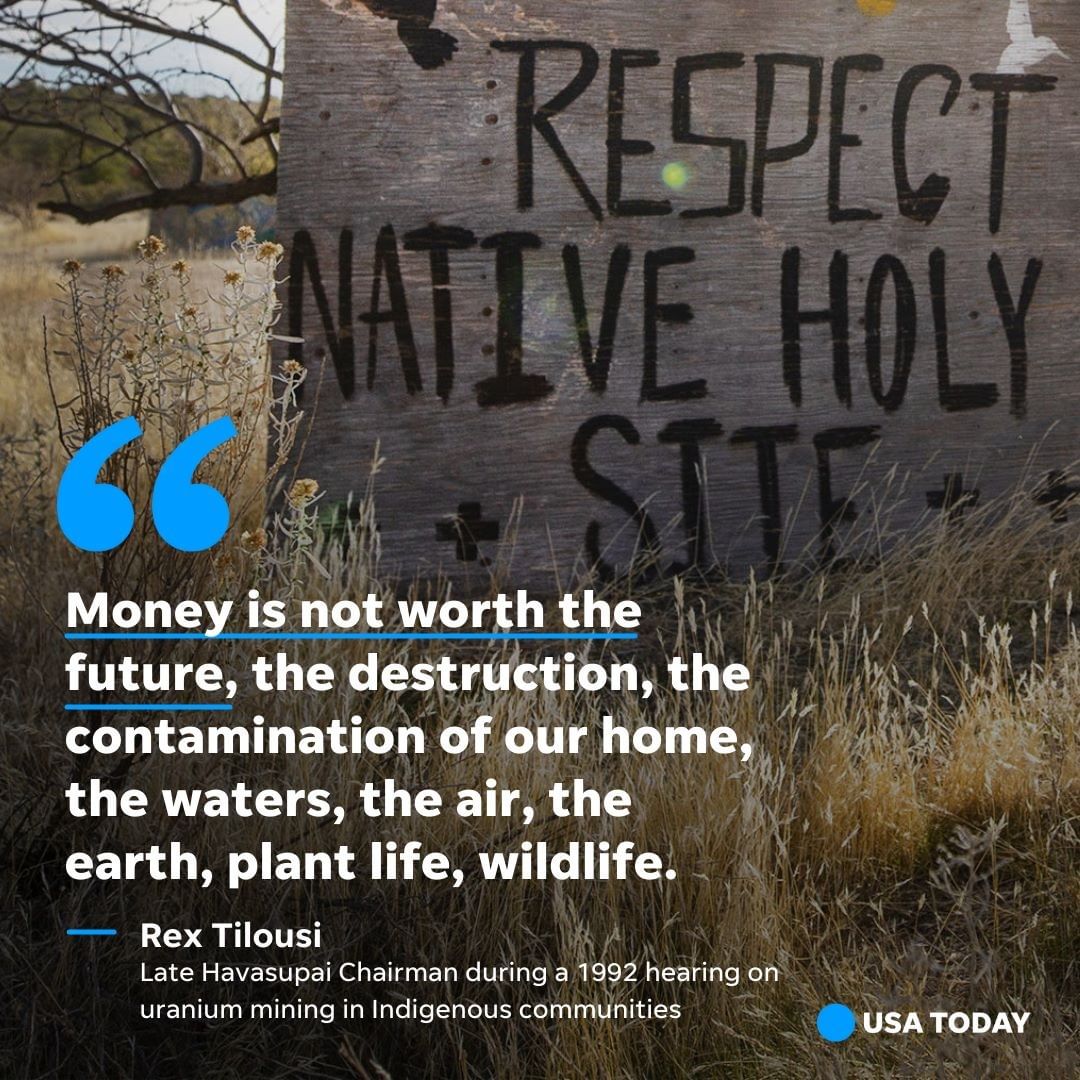

When it comes to protecting sacred spaces off tribal land, tribes are challenged by outdated laws and a misunderstanding of their religious practices.

Native peoples have always regarded certain places, like mountains, springs, particular groves of trees, rock formations or petroglyph sites as sacred spaces. These sites serve as churches, much like synagogues, mosques, temples or other structures serve Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus and other religious communities.

But many of these spaces lie outside of tribal trust land borders, often on public lands. Some of the most well-known places are in Arizona and the southern Colorado River Valley.

Federal laws meant to protect these spaces or Native American religious practices, often come up short. Some legal experts say the federal government seems to practice a double standard when it comes to upholding the religious rights of Native peoples.

Tribes must deal with a revolving door of federal officials and opposition by stakeholders like recreation companies or extraction firms. They also face a lack of knowledge by the public about these places and why Indigenous peoples fight to keep them from harm, or at least further harm.

The Mining Act of 1872 gives U.S. citizens the right to stake claims on federal lands. One claim led to a now-idled mine on the plateau in the vicinity of Mat Taav Tiivjunmdva.

The 750-member Havasupai tribe, the only U.S. tribe that still lives below the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, has long been concerned about the mine. They fear radioactive materials will contaminate their water supply and spoil the sparkling turquoise waters tourists seek out that provide tribal members with their principal revenue source, rendering what's left of their ancestral homeland uninhabitable.

The environmental damage could irreparably alter the ecology of the Canyon, the Havasupai say, and as it worsens, they could perish as a distinct people.

#environment #nativeamerican